When a company wants to affirm its own culture, most of the time it goes through representing, communicating and training around their corporate philosophy expressed as a set of values, competencies and behaviors, the so-called “competency model”.

Looking at the competency model of a company should immediately depict its attitude and vision, showing how they want to appear to the world and face the daily challenges of their market. Core values, ethics, expectations that every company depicts in its model should clearly define its identity and the requirements it has on the managers and employees.

Looking at the competency model of a company will immediately depict its attitude and vision.

A broad spectrum of meanings

However, when there is a need to describe the set of the competencies related to a role, the literature and the plethora of online articles have a very wide range of interpretations around the terms: competencies, skills, behaviors, intentions, attitude, and abilities are very often used as synonyms or correlated in many ways, but there is no constant in assigning the same meaning to the same term.

If you compare the competency model of many companies, you will notice that what someone calls “skill” corresponds to what others call “competence” or “behavior”, depending on the meaning established by the model creator.

There is not always a shared and acknowledged description on the terms, which can generate misunderstandings when it comes to soft skills training.

The concepts of “competencies”, “skills”, “behaviors”, “intentions”, “attitudes”, “abilities” are often used as synonyms or correlated in many ways, showing a lack of a shared and acknowledged description.

Looking for constants

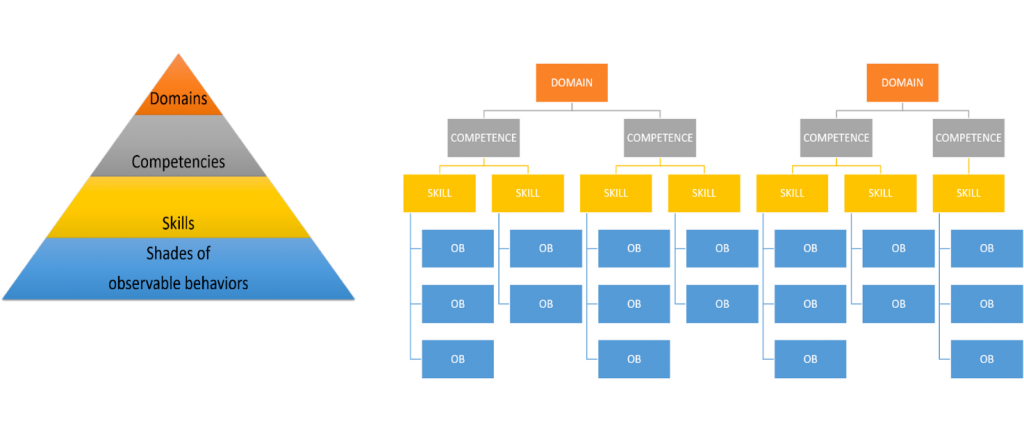

In such a scenario, we notice, however, that there is one constant that connects all the models: the presence of a conceptual hierarchy. A model has many levels of complexity to organize the concepts from the broadest to the most specific one.

Usually the broadest is a domain of competencies or values, and the smallest is related to the observable behaviors expected, that are often declined in different levels of shading from the optimal to the worst one.

For example, a company could value at a broader level the “Communication” domain, which is comprised of many competencies including “Active listening”.

This competency is made of many skills, one of which is “Ask questions” and this skill may have different levels of observable behaviors like “Ask open questions” as the optimal choice, “Ask closed questions” as the sub-optimal and “Not asking questions” as the worst one. When a model has this kind of grading, the levels are usually from 3 to 5.

Let’s try to get things straight

That’s not enough however.

If the aim of a competency model should be that of orienting the behaviors of the people belonging to that organization, such scope is normally addressed by designing soft skills training programs.

Clearly, in order to design and deliver truly effective (and efficient) training, there is a need for a very clear interpretation of the different elements of a competency model in order to be able to conduct the measurement correctly and design training programs that can actually improve the performance of the learner.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines competency as “the quality or state of being competent: such as a the quality or state of having sufficient knowledge, judgment, skill, or strength (as for a particular duty or in a particular respect)”. Similarly, the Cambridge dictionary defines the same word as “the ability to do something well”.

Looking for the term “skill”, the first defines it as “the ability to use one’s knowledge effectively and readily in execution or performance”, while the second states “an ability to do an activity or job well, especially because you have practiced it”.

Both of the dictionaries describe the “behavior” as the fact of managing the actions of oneself in a particular way.

We could continue, but the point is that the meaning of a term in a competency model is given by the interpretation of the authors and its position in the hierarchy.

That’s a good starting point, but let’s delve deeper.

The different building blocks of soft skills training

Let’s try to add clarity with the purpose of better organizing such hierarchy and coming to a clearer picture, thus simplifying the design process of an effective (and actionable) training program.

To do so, it is important to define what the key elements are and how they can be aggregated to create the other ones.

Observable behaviors are the most suitable since they are the components that can be more efficiently and precisely observed and measured. They represent the expression of a skill at particular levels of efficacy, which can be defined using different criteria, as we will see later.

That’s why we can consider them the basic “bricks” that can be re-arranged in competencies and domains to fit the desired competency model.

Observable behaviors, moreover, are the only elements that can be changed, while the elements generated by their aggregation are a representation of one’s style and cannot be directly changed.

Now let’s clarify the most common terms and their meaning, starting from the broader ones, putting them in hierarchical order by defining the meaning of the various terms and the relationship between them.

• A Domain can be considered as a conceptual area that describes a framework of ability applicable to a profession or a role, which expresses one’s capability of doing something in an efficient way in a particular field. This is often fairly broadly identified. In our example, a domain could be “communication”. A domain is made by an aggregation of competencies.

• A Competency can be described as the capability to apply a set of related knowledge, skills and behaviors to successfully perform a critical task in a defined context. In our example, in the domain “communication”, we can identify the competence “Active listening”. A competency is made by an aggregation of skills.

• A Skill is the activity of performing a task, usually pretty precisely described. In our example, under the domain “Communication”, we have the competency “Active listening” comprised by a cluster of skills, one of which is “Ask questions”. A skill shows up in an observable behavior that can be identified in a range of possible manifestations from optimal to worst.

• An Observable behavior is the representation of a skill in a clearly recognizable action in the user. We can identify different levels of efficiency from optimal to worst. In our example, the skill “Ask questions” can have the following grading: “Ask open questions” as the optimal option, “Ask closed questions” as the sub-optimal and “Not asking questions” as the worst one.

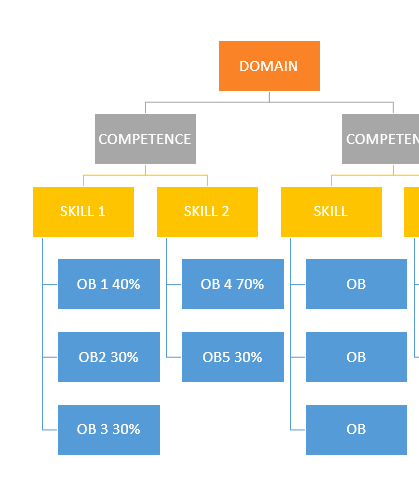

Figure 1: The hierarchy of the elements that make up a competency model

Turning a model into action: from skills to dialogues

As anticipated above, the purpose of a model of competencies that details all the hierarchy from the broadness of the domains to the specificity of the behaviors is twofold:

- On the one hand, it serves to align the resources to an approach that is consistent with the organization’s objectives and vision (and therefore to classify for the purpose of including or excluding some elements)

- On the other hand, is used to have an organized system to evolve people’s behaviors (in order to align them to the expected ones, and to improve the individual and general performance)

To do this, the classical training uses a cognitive approach, which is strongly anchored to knowledge transfer that merely explains the model and the expected behaviors related to it. But since behaviors are acted by people mostly through habits, it is necessary to integrate the cognitive part of the training with a more practical one, which can be done by immersing the trainee in an authentic situation to test, simulate and train individual behaviors.

The ideal learning strategy for doing this is the role play, and even better the Digital Role Play (or DRP, take a look at this article “Digital Role Plays, the Best Way to Develop Conversational Leadership” to learn more) that is more scalable, interactive and less expensive to implement than the traditional face-to-face version.

However, even using an actionable training strategy is not enough to ensure effective skills’ development. In order to be truly effective, any training strategy, especially when devoted to actionable practice such as Role Plays and Digital Role Plays, should embrace in a correct and balanced way all the topics discussed up to this point to efficiently work on the competencies, skills and behaviors deployed by the user during the simulation and to provide a realistic response from the virtual character.

Let’s take, for example. the case of how a competency model can be useful in the design of a truly actionable training tool on soft skills such as a Digital Role Play.

We have said that observable behaviors are the basic bricks and also the most important components of a hierarchy of a competency model, since they are the only ones that can actually be measured in a direct way through observation and can be modified through a repetition and feedback-based training process.

The first step is to decide how many levels of grading we will be using: usually the final result is 3 to 5 levels. Based on my experience, 5 is the best compromise since it lets you have the right amount of specificity for each grade whilst keeping a reasonable amount of granularity.

In addition to this grading, which generally describes the worsening of a behavior, a skill can be also turned into a different cluster of observable behaviors that bind to each other with different grades of effectiveness with respect to a goal.

In our example, the skill “ask questions” can have as its optimal “ask open questions” if you want to explore a topic, but if the situation is different and you need to analyze and classify something, the optimal behavior would be “ask closed questions”.

To be able to order the behaviors correctly, it is necessary to apply a series of criteria (I normally use the 6 listed below) which allow for the contextualization of the reasons for which a certain behavior is optimal or not, according to a set of rules of grading:

- The character we are meeting

- The type of conversation we are managing

- The topic of the meeting we are in

- The scope of the measurement

- The seniority of the user

- The time when we use it (at the beginning of the conversation, in the middle, at the end, etc.)

Having a situational approach here is one of the key factors to success, as we have said for the leadership in another article (“Using Situational Leadership to Manage Different Types of Conversations”).

The most important elements to work on in the Conversational Leadership training are observable behaviors, as they are the measurable expression of a skill at a particular level of efficacy.

The application in a Digital Role Play

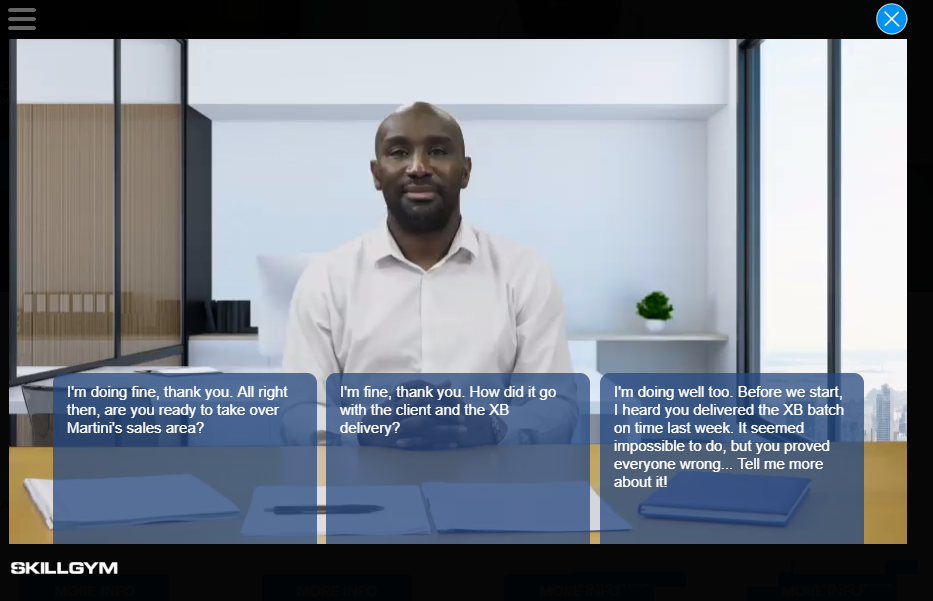

In a digital role play, these gradings and shadings are usually represented by a very well-designed set of sentences available to the user as options to choose from along the dialogue, where the user is requested to select the one he feels closer to his real-life approach.

The experience is designed in a way that the skills involved are checked multiple times and in the different shades along the story, to provide a precise and weighted measurement of the actual and situational behaviors acted by the user.

Every step of the conversation is bound to one or more skills, guiding the writing of the available options in a way that the storytelling becomes a trigger to action and trains the existing user’s skills in such a subtle way that is invisible to the user, thus also making this methodology suitable for assessment purposes.

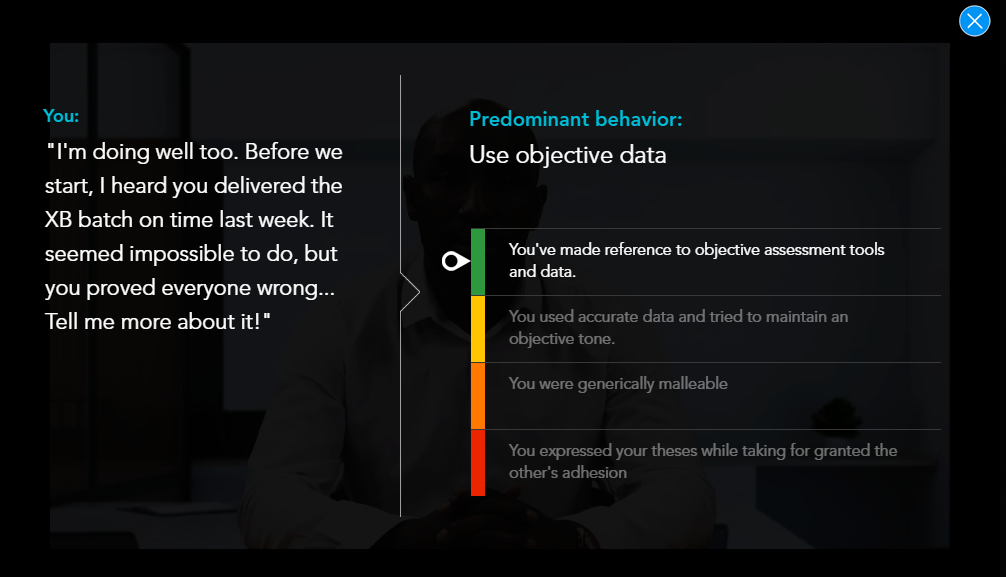

In the following image, we can see an example where the user can act the skill “Use objective data” in an optimal, sub-optimal or wrong way according to a mix of the above 6 criteria defining the reasons of such a rating and ranking.

Figure 2: An example of the interaction with a virtual character

Learning from the situation

Using Digital Role Play to show how the concept of observable behavior can be graded and shaded in a training tool to turn it into an actionable learning-by-doing strategy is even more interesting when we consider those Digital Role Plays that allow the option of reviewing a previously played interview and providing the trainees with information about where, when and how certain behaviors were acted (you can check this article “Digital Role Play Stripped Bare” which explains the different phases of the DRP-based training method).

In such case, the meta-narrative strategy to build the sentences of the dialogue (see this article “The True Learning Scope Behind a Digital Role Play” for more details on this approach) can be fully exploited in pedagogical terms by helping the trainees to track a line between their choices and the underlying behaviors (and then up to competencies and domains).

We refer to this as “reverse engineering”.

In the image below, you can see how the explanation of the observable behavior measured according to its qualitative grade for this specific context is given during the review (“replay”) of a conversation.

Figure 3: The sentence as an expression of a skill at a particular grade of efficacy, as shown in the replay

This kind of user experience can be leveraged to design emotional storytelling that helps people to practice behaviors, which are the contextualized in everyday life, as well as to measure their efficacy by providing valuable feedback, both qualitative (in the post-meeting feedback by the character) and quantitative (in analytics and Augmented Replay).

The outcome of this training made by a looping sequence of experience, feedback, reasoning and re-experience leads to an evolution of the trainees’ behaviors and therefore the overall quality of the skills of the Leaders and, as an effect of it, of the entire organization.

The importance of behavior mapping

Still within the context of this practical training application of a competency model, a good question to move forward on would be: what criteria should be used to connect the competency model to the design of a Digital Role Play?

There are several elements to be considered here, but the primary component is increasing effectiveness training. This is accomplished when it is designed as situational while taking into account the mix of variables that define the “situation” in order to understand which skills can reasonably be linked to the exercise.

You have to identify the most important skills to train by selecting the ones that, if well managed, lead to a better performance in the role’s KPI.

Here are some criteria to identify the skills set:

- The type of conversation

- The topic of the conversation

- They type of character with which the conversation is taken

- The role of the trainees

Those elements define the situation and each situation shall be dealt with in a preferred leadership style, which will attract certain skills and relevant behaviors. Then, once the skills are identified, the plot will be developed (what turns a situation into an actionable story) by turning well-graded and well-shaded behaviors into storytelling dialogues.

Grading and shading of the behaviors can be done using the six criteria shared above.

When designing the dialogue, it is very important to assign one or more skills to each passage, ensuring that every skill is checked multiple times (around 10) along the entire story to ensure a more precise measurement.

An important consideration to keep in mind is that the weighted aggregation of behaviors in the skills must be done at the time the DRP is designed, since it is strictly related to the meta-narrative of the storytelling.

After that, it is always possible to re-aggregate the skills in personalized competencies models through an analysis of the meaning of the individual behaviors of a skill and of the skills themselves. To explain this point, let’s see what happens when you choose ready-made Digital Role Plays and you need to connect the trained behaviors (and skills) to your personalized competency model.

In this case, we start from the skills and their shades of behaviors, and we connect them to the competencies possible in a well-weighted manner.

Every skill is made by two or more observable behaviors (OB) that contribute to the score of their related skill with different weights. They can have more or less the same importance as you see in Figure 4 on the left or there can be an OB way more important than the other(s) like you can see on the right (expressed in weighted percentage).

Figure 4: Observable behaviors with different degrees of importance are aggregated to create a skill

The upward aggregation of skills into competencies can be done by analyzing the meaning associated with the skills (and to the subsequent observable behaviors) and searching which skill(s) can contribute to the description of a certain competency.

Since skills (and, more so, observable behaviors) are the most elementary piece of the model, it is normally quite easy to find a way to bring several skills together to match the content of a competency. As we have seen, this operation can be done by excluding, aggregating and balancing the available skills in the desired competencies.

Conclusions

Let’s draw a conclusion.

On one side, in order to provide an actionable meaning to a competency model, whatever it is, it is paramount to clarify the meaning of each of its components and, most of all the relationship between the different building blocks.

On the other side, it is important to relate the entire competency model to some actionable form of measurement and development, to make sure that people in the organization can recognize it as a meaningful way to orientate behaviors along the way.

The most actionable learning strategies normally come with some sort of role-playing, such as Digital Role Play. When the design of such tools is well crafted, it is quite straightforward to leverage the smallest bricks of a competency model to develop powerful soft skills training solutions that fit any model upwards.

Finally, it is therefore fundamental to carefully choose those Digital Role Play solutions that work on observable behaviors that are well aggregated in a comprehensive skill map, since they can be more easily integrated into proprietary competency models.

If you are interested in learning more about designing a balanced curriculum for training soft skills in an actionable way, I would recommend reading this article (“A Curriculum for Conversational Leadership”).

Of course, we would be delighted to show you SkillGym’s solution in a 1-hour discovery call.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• On classifier domains of competence, E.B. Mansilla; Tin Kam Ho. Check here

• What Is Competence? FRANCOISE DELAMARE LE DEIST & JONATHAN WINTERTON, Human Resource Development International, Vol. 8, No. 1, 27 – 46, March 2005. Check here

• University of Texas School of Health. Check here

• Toward a Common Taxonomy of Competency, Domains for the Health Professions and Competencies for Physicians. Robert Englander, MD, MPH, Terri Cameron, MA, Adrian J. Ballard, Jessica Dodge, Janet Bull, MA, and Carol A. Aschenbrener, MD. Check here