This article has been co-written with Elena Ciani, Neuropsychologist

What is cognitive neuroscience and why is it important in adult learning?

Cognitive neuroscience can be considered both a branch of psychology and neuroscience. It studies the biological processes and the neural connections in the brain that regulate human cognition and mental processes.

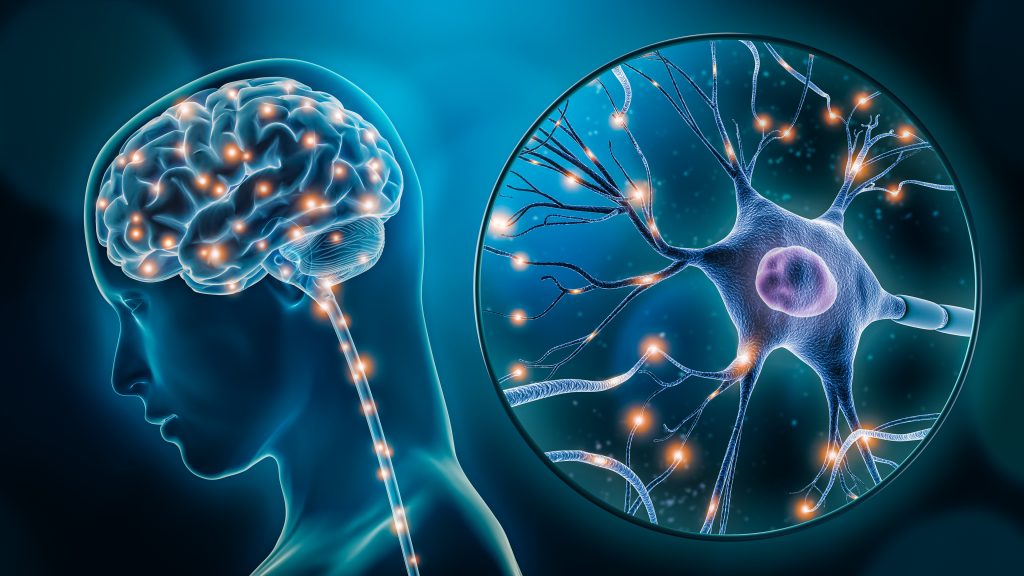

The ability to learn, that can be expressed like the ability to establish causal relationships between events and to modify one’s behavior based on these experiences, is made possible by the particular organization of our nervous system.

It consists of about 100 billion neurons, each of which establishes tens of thousands of contacts with other neurons through the synapses.

The term synapse (that was introduced in 1879 by the English physiologist Sherrington) describes the junction between two neurons, specialized in the transmission of the nervous impulse.

Today it is widely demonstrated that learning and experience can induce a permanent modification of the connections between neurons, at the level of the synapse.

So, from a biological point of view, learning corresponds to the formation of a new network of connections between neurons, and to the modification of pre-existing synaptic connections. When information passes several times through the same sequence of synapses, the path is facilitated and reinforced.

Learning, a key process of our brain, continues throughout life and is based on memorization. Memory supports the process of acquiring information and allows it to be recovered when necessary. But memorization would not start without the fundamental mechanism of attention that underlies all learning.

Neurologically, “attention is the brain’s ability to privilege electrical signals related to a given experience, dropping all others” (P.Rivoltella) [1].

Learning corresponds to the formation of a new network of connections between neurons, and to the modification of pre-existing synaptic connections

Basic emotions and their biological roots

Charles Darwin was among the first to believe that emotions had biological roots, and that there were remarkable similarities between the emotional mechanisms of animals and those of human beings. He studied the physiology of some emotions, describing them from activated muscles to reactions such as the production of tears, changes in breathing, heart rhythm, etc.

The theory of Darwin has had several confirmations: for example, in all cultures the facial expression of some emotions are very similar, as also Eibl-Eibsefeldt or Ekman have shown.

Emotions also involve other innate mechanisms that make facial expressions correspond to changes in the “internal state” of the organism. For example, Ekman has shown that if an actor recites an emotion, some physiological parameters such as cardiac rhythm or breathing change.

The brain, in other words, is deceived by the facial expressions.

Many modern theorists like Sylvan Tomkins, Carroll Izard, Paul Ekman, Robert Plutchik, Nico Frijda and Jaak Panksepp identified a set of fundamental and innate emotions, defined by facial expressions and other body parts movements.

Despite the unavoidable cultural differences, these expressions (especially the facial ones) are similar in many different cultures. Moreover, according to Plutchik, as you go down the evolutionary scale, facial expressions become increasingly rare, while there are still many emotional expressions involving other body systems.

If we try to summarize their studies by identifying a common ground, we could identify this set of basic emotions:

- Surprise

- Fear/anguish

- Joy/happiness

- Anger

- Disgust

- Shame

- Interest

Non-basic emotions

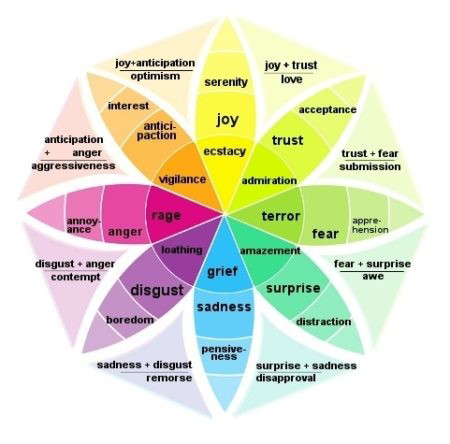

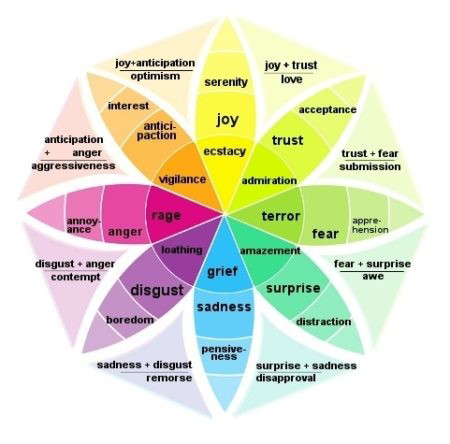

Most fundamental emotion theorists believe that there are also non-basic emotions that are a result of a mix of the basic ones. We believe that one of the best representations of this can be found in the “wheel of emotions” by Plutchik, that depicts the emotions as colors arranged on a circle.

Every elementary emotion of his model is represented as a segment of the circle, and two merging segments are called dyads. When two adjacent emotions merge, they are dyads of the first order; if two emotions are separated by a third, they are second-order dyads, and so on. The further away two elementary emotions are, the less likely they are to mix.

For example, love is a first-order dyad since it merges joy and trust, the same for aggressiveness who mixes anticipation and anger.

Guilt, however, is a second-order dyad since it merges joy and fear, which are separate from acceptance.

Figure 1: Plutchik’s wheel of emotions (source)

According to many theorists, even animals can have biologically elementary emotions, but the difference with the human beings is that the latter can also elaborate and experience derived or non-elementary ones.

The act of merging basic emotions into higher-order emotions is usually considered a cognitive operation, and since human cognition is the most complex of all the other mammals, emotions like pride, shame and gratitude could be exclusively human (R.Lazarus).

How emotional experiences impact on our reactions?

At this point the framing of our reasoning should be clear, so let’s delve a little more: to understand how emotional feelings are created, and how do they impact on our immediate and automatic reactions, we must understand how emotion systems work and see how their activity is represented in our working memory.

Let’s look together at an example on how the emotion of fear comes up in our mind if we see, for example, a snake instead of a rabbit, by going together through a very famous passage of Joseph LeDoux in his book “The Emotional Brain. The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life “.

Please pay particular attention to the parts that are in bold, since we are going to recall them later:

You encounter a rabbit while walking along a path in the woods. Light reflected from the rabbit is picked up by your eyes. The signals are then transmitted through the visual system to your visual thalamus, and then to your visual cortex, where a sensory representation of the rabbit is created and held in a short-term visual object buffer.

Connections from the visual cortex to the cortical long-term memory networks activate relevant memories (both facts about rabbits stored in memory as well as memories about past experiences you may have had with rabbits).

By way of connections between the long-term memory networks and the working memory system, activated long-term memories are integrated with the sensory representation of the stimulus in working memory, allowing you to be consciously aware that the object you are looking at is a rabbit.

So, in this part LeDoux emphasizes how the “hardware” and the “software” of our brain interact in a typical situation. But let’s continue to see where, how and why the emotion is created.

A few strides later down the path, there is a snake coiled up next to a log. Your eyes also pick up on this stimulus. Conscious representations are created in the same way as for the rabbit – by the integration in working memory of short-term visual representations with information from long-term memory.

However, in the case of the snake, in addition to being aware of the kind of animal you are looking at, long-term memory also informs you that this kind of animal can be dangerous and that you might be in danger. According to cognitive appraisal theories, the processes described so far would constitute your assessment of the situation and should be enough to account for the ‘fear’ that you are feeling as a result of encountering the snake.

The difference between the working memory representation of the rabbit and the snake is that the latter includes information about the snake being dangerous. But these cognitive representations and appraisals in working memory are not enough to turn the experience into a full-blown emotional experience.

Something else is needed to turn cognitive appraisals into emotions, to turn experiences into emotional experiences. That something, of course, is the activation of the system built by evolution to deal with dangers. That system, as we’ve seen, crucially involves the amygdala.

Many but not all people who encounter a snake in a situation such as the one described will have a full-blown emotional reaction that includes bodily responses and emotional feelings.

This will only occur if the visual representation of the snake triggers the amygdala. A whole host of output pathways will then be activated. […] [3]

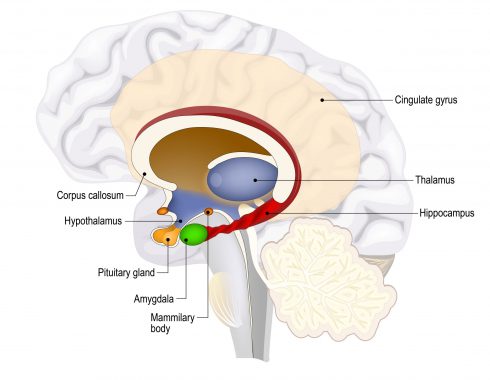

Activating the limbic system

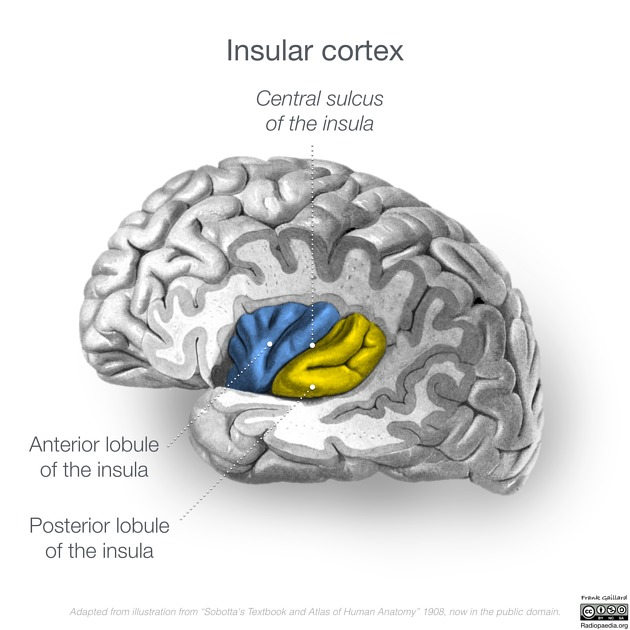

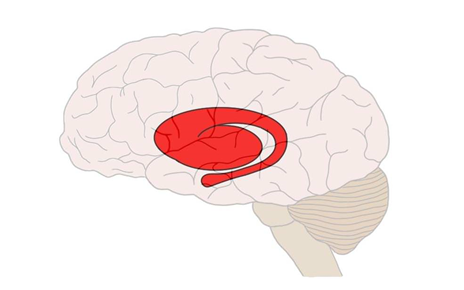

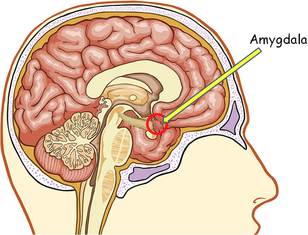

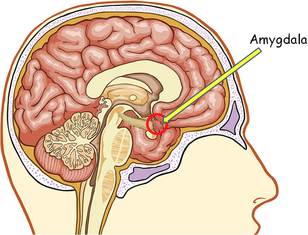

It should be clear now how the emotions are strictly connected to the biological elements related to their functioning, and in particular to the amygdala, that is an almond-shaped set of neurons that is proved to play a key role in processing some emotions like fear and aggressivity, and together with hippocampus hypothalamus, fornix, limbic cortex and other structures forms our limbic system.

The amygdala in particular induces vegetative reactions like increased heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, etc. and hormonal reactions like the adrenal one.

Moreover, it receives information from the thalamus even before they arrive to the cortex: this means that the emotion can take place before we have time to start thinking about it.

Figure 2: The location of the amygdala in the human brain (source)

But how does the activation of amygdala turns a normal experience into an emotional experience? As LeDoux says, what makes the encounter with the snake an emotional experience is the mix of 3 things that happen in our working memory:

- the (short-term) sensory representations

- the (long-term) memories activated

- some “outputs” that we will now list:

- Direct Amygdala Influences on the Cortex: To reach the amygdala, a visual stimulus has to go through the primary cortex, to a secondary region, and then to a third cortical area (the one where short-term buffering of visual object information takes place). The amygdala projects back to all those three visual processing regions.

As a result, once the amygdala is activated, it is able to influence the cortical areas that are processing the stimuli that are activating it. The connections from the amygdala to the cortex allow the it to influence attention, perception, and memory in situations where we are facing danger.

- Amygdala Triggered Arousal: When arousal occurs, cells in the cortex, and in the thalamic regions that supply the cortex with its major inputs, become more sensitive. Arousal is important in all mental functions. It contributes significantly to attention, perception, memory, emotion, and problem solving. Without arousal, we fail to notice what is going on—we don’t attend to the details. But too much arousal is not good either.

You need to have just the right level of activation to perform optimally. If you are over aroused, you become tense and anxious and unproductive. Emotional reactions are typically accompanied by intense cortical arousal.

Emotion and cognitive processes

Let’s start saying that the 8 main cognitive processes of the human beings are:

- Perception

- Learning

- Language

- Thought

- Attention

- Memory

- Motivation

- Emotion

Numerous studies have reported that most of all human cognitive processes including memory and learning (Phelps, 2004; Um et al., 2012), attention (Vuilleumier, 2005), problem solving (Isen et al., 1987) are affected by emotion.

Attentional component of emotion has been linked to enhanced learning and memory performance.

Therefore, emotional experiences/stimuli appear to be remembered vividly and accurately, with great resilience over time [7].

But how does it happen?

Taking in mind that hippocampus and amygdala are both part of the limbic system, cognition and emotion processes are operated at two separate but interacting systems:

(i) the “cool cognitive system” is hippocampus-based that is associated with cognitive functions, and cognitive controls. Hippocampus has a critical role in formation, organization and storage of new memories.

(ii) The “hot emotional system”, as mentioned above, indeed is amygdala-based. In addition, an early view of a dorsal/ventral stream distinction was commonly reported between both systems.

The “cool system” for active maintenance of controlled processes such as cognitive performance and pursuit of goal-relevant information in Working Memory, seems to involve the Dorsal Stream: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex DLPFC and Lateral parietal cortex).

In contrast, emotional processing systems involves ventral neural system such as: amygdala, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), orbitofrontal (OFC) and occipito-temporal cortex (OTC) (Dolcos et al., 2011).

Nonetheless, recent investigations claim that these two different cognitive and emotional neural systems are not separated but are deeply integrated. Consequently, lots of studies show that emotions influence the formation of a hippocampal-dependent memory system (Pessoa, 2008), and it has a long-term impact on learning and memory.

In other words, even if cognitive and affective processes can be independently conceptualized, it is not surprising that emotions powerfully modify cognitive appraisals and memory processes and vice versa (Chai M.T. et al., 2017).

Recent advances in affective neuroscience and emotion research confirmed that the human mind is continuously emotional (Izard, 2009, Lewis, 2005, Tucker, 2007), Cognition and emotion are inherently interconnected.

This interconnectedness is an essential aspect of the complexity of human consciousness. An important quality of this interconnectedness is that emotional activity enables and sustains cognitive activity, including mechanisms that are central to learning (Plass et Kaplan, 2016).

Empathy and mirror neurons

Let’s imagine that someone tells you about an accident in which a person was seriously injured. It may happen that, for a moment, you feel a sensation of pain that reflects in your mind the pain of the injured person.

This feeling can be more or less intense, depending on the scale of the accident or your knowledge of the person involved. The mechanism that is supposed to produce this sort of feeling is a variety of what A. Damasio called the “as if” body circuit.

It implies an internal simulation at cerebral level which consists in the rapid modification of the maps of the current state of the body, where the brain temporarily creates a set of maps that do not correspond to the real state of the body, but to the simulated one.

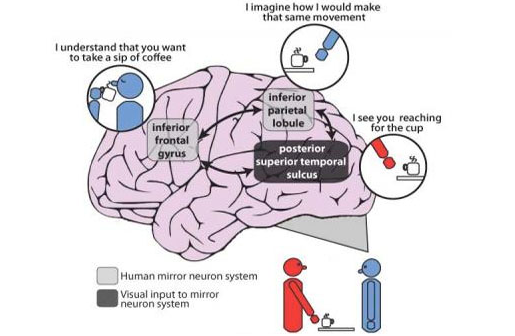

This happens when certain brain regions, for example the prefrontal or premotor cortex, report directly to the somatosensory regions of the brain. The involved neurons can represent, in a person’s brain, the movements that he sees in another individual, and send signals to the sensorimotor structures so that the corresponding movements are “previewed” in a simulation mode, or actually performed. These neurons are actually present in monkeys and humans, and are known as “mirror neurons”.

The result of the direct simulation of the body states in the somatosensory regions is not different from that of the filtering of signals coming from the body.

The brain uses the signals from the periphery to create a particular state of the body in the regions where it is possible to construct such a representation, i.e. in the somatosensitive regions. What one feels, then, is based on that “false” construction, and not on the “real” state of the body.[4]

When these specialized neurons are activated, other areas of our brain, such as the limbic system, are also activated.

This allows us to recognize facial expressions, access our memories and previous learning and combine all this information to interpret the situation and give it meaning. On these neurons is based not only the justification of some forms of apprenticeship where the novice learns alongside the expert, but also the possibility of understanding how learning always passes through body simulation: this is what the studies of Vittorio Gallese on the ability of cinema, and image in general, to activate our mirror circuit.

According to what Gallese, Keysers and Rizzolatti have argued, these mirror mechanisms “allow us to directly understand the meaning of the actions and emotions of others by replicating them internally or simulating them without any explicit reflexive mediation”[5]. This emphasize the fact that conceptual reasoning is not necessary for this form of understanding of actions.

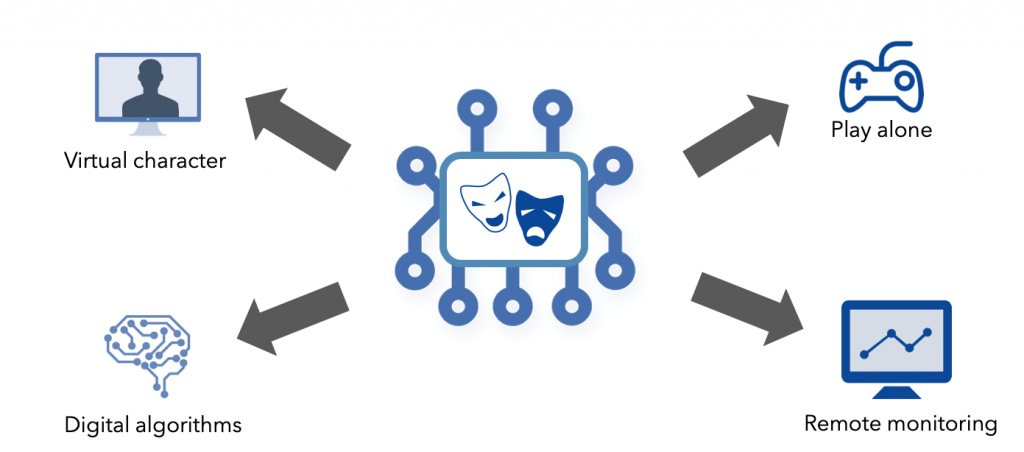

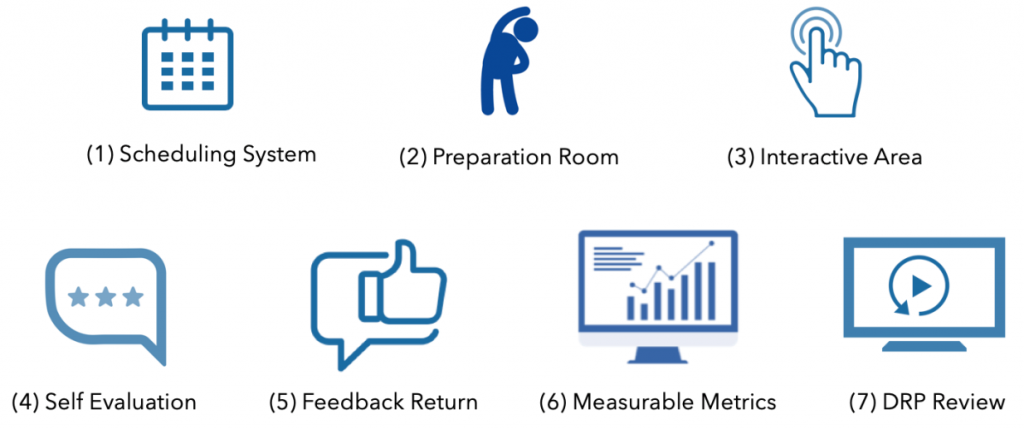

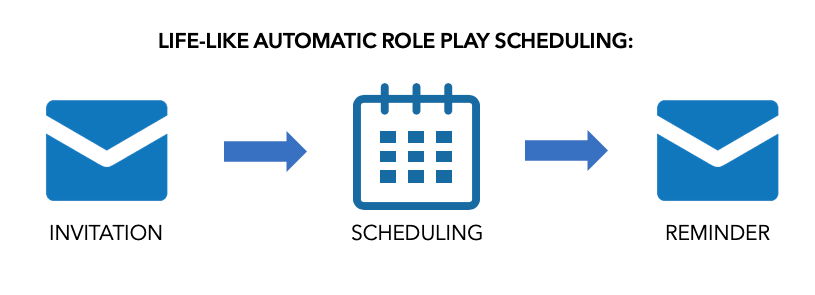

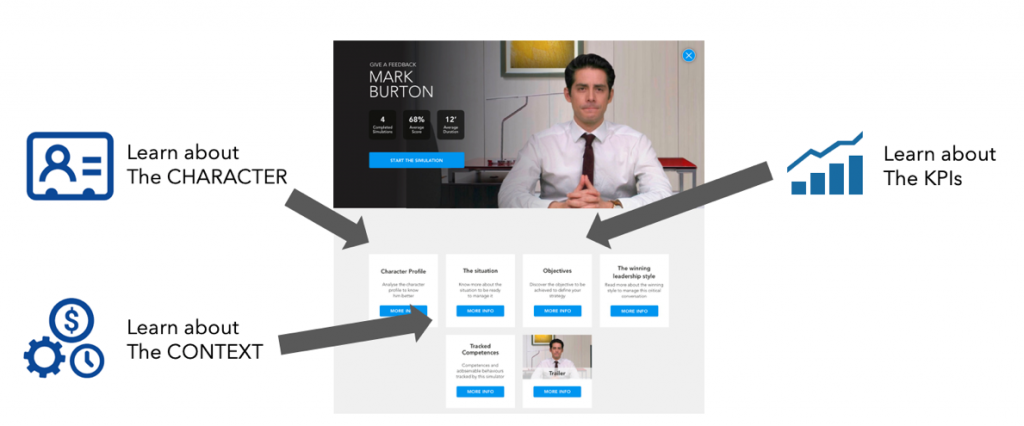

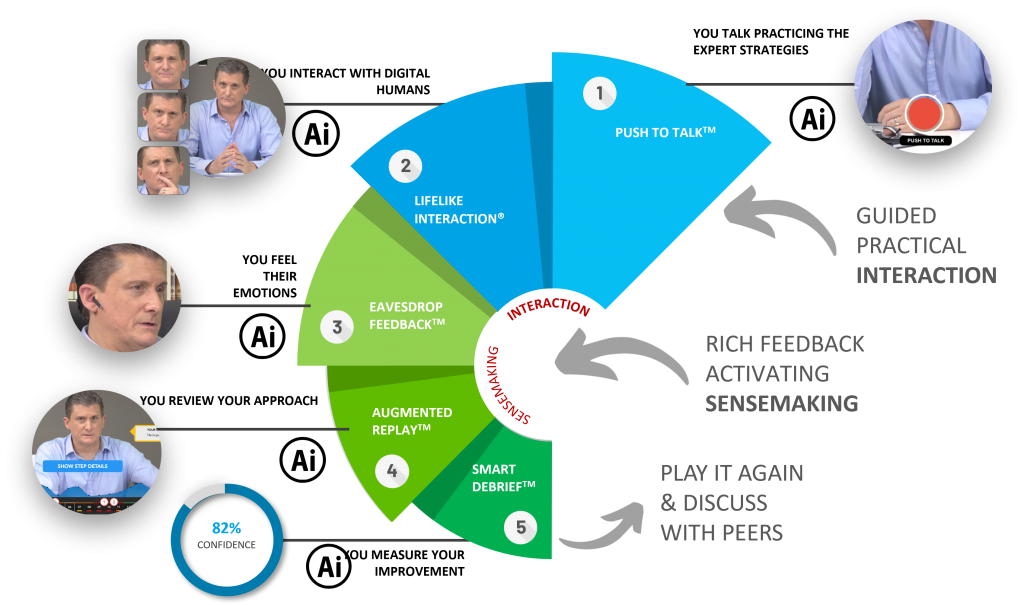

Here at Lifelike we have published another interesting article about the impact in learner’s mind of a simulation, and in particular a digital roleplay. If you want to deepen this topic check out this article (“Our Brain Doesn’t See the Difference Between Simulation and Reality”).

Neurosciences and simulations

Emotions are reactions to external stimuli that allow us to guide our behavior and act quickly when we receive requests from the surrounding environment.

They are made of 3 components: somatic, behavioral and feeling. It is important to remember that any decision is conditioned to a greater or lesser extent by our emotions. [2].

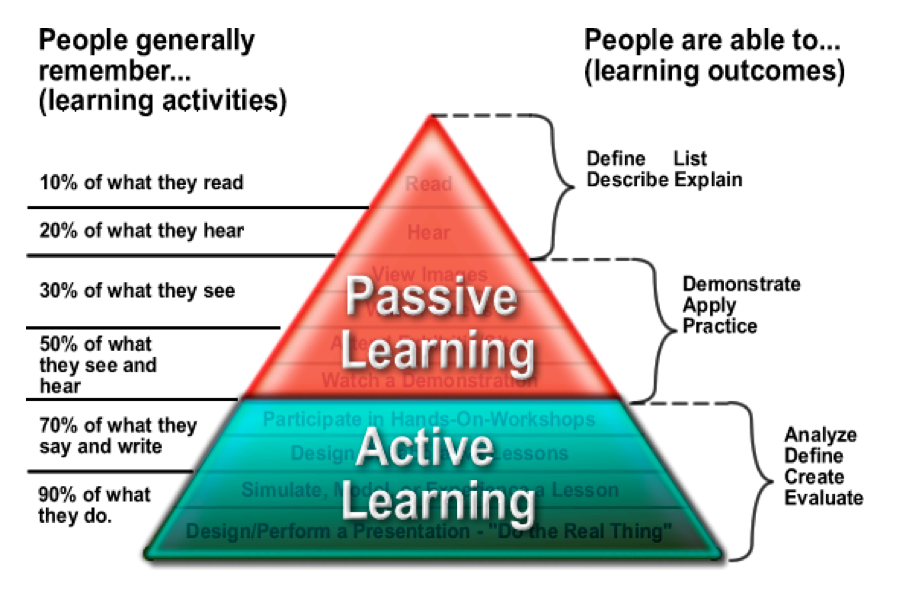

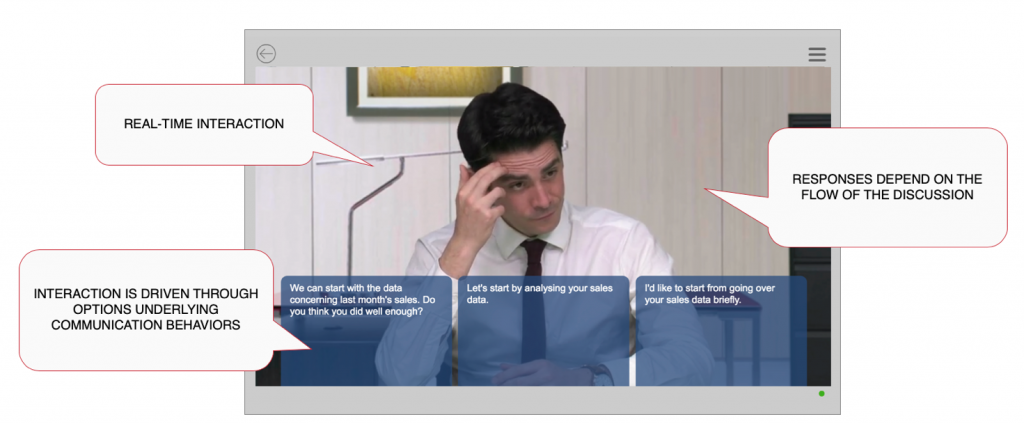

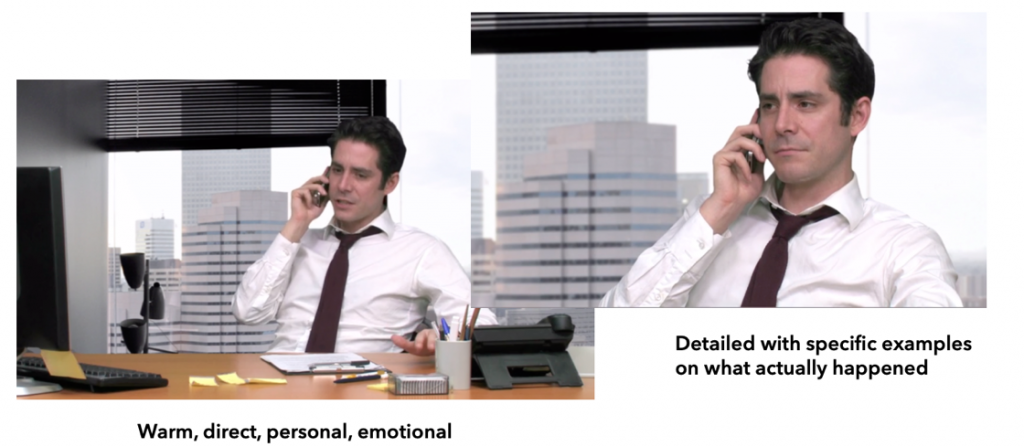

Emotional experiences (including simulators and digital role plays) actually have an important effect at a biological level, and stimulate fast reactions even thanks to the fact that they involve the amygdala.

We also know that human brain tends to save energy and minimize the use of conscious reasoning, that requires considerable effort. To achieve this goal, it generates neural routines, behavioral automatisms that do not require the intervention of awareness because the brain has already set up, based on experience, a set of automatic responses.

So, through emotion, we generate what Damasio calls somatic marker: [6] that pleasant or unpleasant feeling felt by the individual when the outcome (positive or negative) connected to a specific option comes to his mind.

But the two moments are not alternative: the acquisition of new information is connected with involving emotional experiences, and a plurality of information anchors will be generated and will allow a faster and easier recall. The emotional contents of an experience, therefore, represent an indispensable reinforcement for a good memorization.

The emotional contents of an experience represent a reinforcement for a good memorization

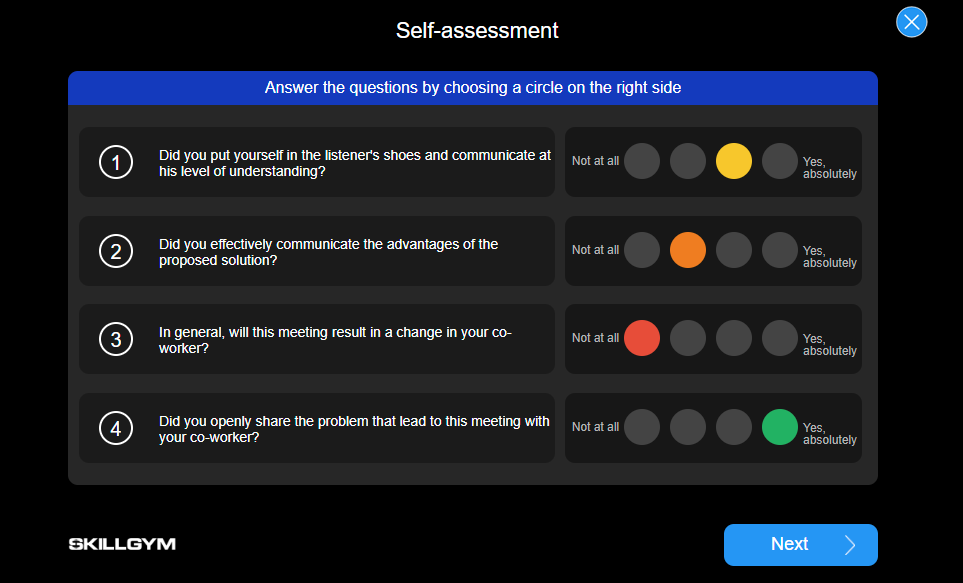

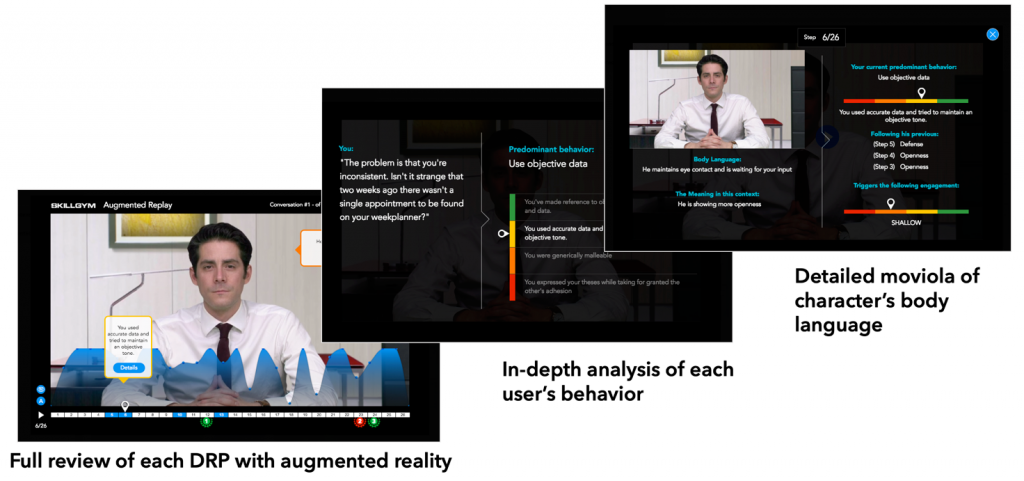

The importance of feedback in simulations

Another basic mechanism of the brain is the feedback, who generates a self-regulation that the person does, based on his experience with the environment and the other people. In other words, the acquisition of good behaviors occurs through the response that each of us has from the environment and the relationship with people, and especially in the detection of the inevitable errors and mental traps we incur physiologically.

Our brain learns more from denials than from confirmations; the error is, therefore, a valuable opportunity for learning. If you want to do deepen all the learning scope of a simulated experience, we suggest you this interesting article: The true learning scope behind a Digital Role Play.

Bibliography

[7] Chai M.T. et al (2017) The Influences of Emotion on Learning and Memory. Front. Psychol.

Dolcos, F., Iordan, A. D., and Dolcos, S. (2011). Neural correlates of emotion–cognition interactions: a review of evidence from brain imaging investigations. J. Cogn. Psychol. 23, 669–694. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2011.594433

Plass J.L, Ulas Kaplan, Emotional Design in Digital Media for Learning, pg 131-161, 2016)

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., and Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 1122–1131. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1122

Pessoa, L. (2008). On the relationship between emotion and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 148–158. doi: 10.1038/nrn2317

Phelps, E. A. (2004). Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015

Um, E., Plass, J. L., Hayward, E. O., and Homer, B. D. (2012). Emotional design in multimedia learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 485–498. doi: 10.1037/a0026609

Vuilleumier, P. (2005). How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011

The reactions generated while stimulating the amygdala are faster than the ones generated when we use the parts of the brain that act rationally. Moreover, the use of emotions in training has been proven to improve retention and recall of what has been learned.

The reactions generated while stimulating the amygdala are faster than the ones generated when we use the parts of the brain that act rationally. Moreover, the use of emotions in training has been proven to improve retention and recall of what has been learned.

Learning theories.

Learning theories. Psychometric models.

Psychometric models. Communication styles.

Communication styles. Soft Skills.

Soft Skills.